Type ‘civilisation’ into the search bar of Google and three of the five suggested searches relate to the long-running computer game. The other two are ‘civilisation meaning’ and ‘civilisation definition’. Somebody somewhere has clearly been thinking and wondering, as well they might. Hit the enter key and, putting aside the game and a TV mini-series and a book by a professor of Fine Art, you have the offerings of Wikipedia and two online dictionaries.

Good old Wiki first:

A civilization (UK and US) or civilisation (British English variant) is any complex society characterized by urban development, social stratification, symbolic communication forms (typically, writing systems), and a perceived separation from and domination over the natural environment by a cultural elite.

Even with accompanying photos of the pyramids and Aristotle, I’m not sure that makes much of a sales pitch. A complex society (i.e., basically, division of labour into specialisations) I’ve nothing against, and to writing systems I’d be the last to object. But I can’t summon much enthusiasm for urban development if what I see from my window is anything to go by, or for an entrenched class system – or ‘social stratification’, to give it the impersonal and geological-sounding term which suggests a process of nature rather than of man. ‘Domination over the natural environment’ has been in the news quite a lot recently:

Here’s a dominated natural environment:

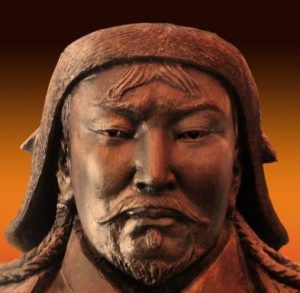

And that would make this the cultural elite:

The two online dictionaries make the whole thing sound a bit more promising:

An advanced state of human society, in which a high level of culture, science, industry, and government has been reached.

An advanced state of intellectual, cultural, and material development in human society, marked by progress in the arts and sciences, the extensive use of record-keeping, including writing, and the appearance of complex political and social institutions.

High level of culture, intellectual development – that must be what our advanced governments defend on our behalf with our reluctant but salutary bombs, eliminating alleged threats to ‘our way of life’ without ever specifying what our way of life actually is.

This is all easy enough to say, of course, and to answer. After all, “that’s how the world works”, “it’s always been the same everywhere” et cetera ad nauseam. But before you decide there’s nothing to see here and it’s time to move along, let us for a moment consider some barbarians. Maybe it was not always the same everywhere. The obvious choice would the indigenous Americans (ancestors of those recently attacked by militarised police for trying to defend drinking water from oil), who had no class system and regarded rapacity as a sickness: ‘wetiko’, a sort of spiritual cannibalism unperceived by the sufferer who saw nothing wrong or irrational about enriching himself in ways that made the existence of others impossible or unbearable. The first Europeans to bring them civilisation and ‘our way of life’ had a hell of a time trying to make them comprehend that land was a possession to be dominated and owned, that men were subject by birth to an elaborate grading system, and that women were of no possible function in society beyond the reproductive and ornamental. And the myth of the ‘wild’ and ‘savage’ ‘jungle’ has endured to this day because the ‘civilised’ coloniser mind could not perceive or conceive a sustainably managed ecosystem in any land not flattened and fenced – or, you might say, not dominated. But those peoples have a long-established reputation as some kind of proto-hippies, so that also would be too easy. And it’s not of them that I think whenever I see or hear any of the human offal recently brought to power by ballot-enabled coups on each side of the Atlantic.

So take instead the barbarian of barbarians, a name synonymous with blood and terror and savagery, because every time I see a Michael Gove telling the mob that we’ve “had enough of experts”, or a Theresa May introducing immigration policies that deport and lock out teachers and nurses while letting in princelings and bankers, or Agent Orange trying to abolish healthcare for the poor or to discredit science, I think of Genghis Khan. (The pronunciation, by the way, has been lost in the English spelling: it should be “Chingiz” with a hard ‘ch’.)

When a city fell to his Mongols and the keys were, literally or metaphorically, handed over with the plunder set to begin, he delegated to others all that concerned material riches. The money would be channelled into the sponsorship of trade, and the sumptuous clothes and jewellery would be sent back to the steppe for the amusement and adornment of young girls milking yaks. He took a personal interest in one thing only: experts. Who were the place’s architects, engineers, scientists, mathematicians, teachers, doctors, master builders and so on? Ensuring they were added to the payroll and incorporated into the empire demanded his personal attention. Any self-respecting Mongol could ride and shoot, but civil expertise was also needed and was rewarded when found. The previous rulers, if they had no skill to recommend them, would be detailed as manual labour alongside those who had been menially serving them till the day or the hour before. He was clearly not a Tory. Teachers and doctors, indeed, were exempt from taxation, on the basis that even an idiot would understand you can never have too many of them.

This, be it remembered, was from a man who could not read or write so much as his own name, whose childhood peer group had consisted of horses, who had endured brute slavery and the abduction and rape of his wife, who had killed his half-brother to prevent him marrying his mother, and who only once in his life is recorded as having entered a walled and roofed building. Yet if civilisation really is, to take definition #5 from thefreedictionary.com, ‘intellectual, cultural and moral refinement’, he had a better understanding of it than those currently leading the western world. He was almost certainly the first ruler to promote universal literacy, to demonstrate almost total racial and religious tolerance, and to reject nepotism for a genuine meritocracy. And having as a boy been effectively abandoned to starvation, he knew hunger in its reality: a leader of nomadic cavalry was hardly in a position to set up a welfare state, but for a Mongol to eat in front of another and fail to offer him any was made punishable by death. A touch extreme, perhaps. But in modern Britain, one of the richest countries in the world, where about 1 in 65 people is estimated to be a millionaire, more than half a million others, employed and unemployed alike, are now dependent on charity-run food banks. Would it not seem to any reasonable person that something of fundamental importance has been lost here? After all we are taught from infancy to believe about civilisation (definition #5 above), is it really a position of extremism to suggest that we are now operating at a lower level of it than people eight centuries ago who could not write or spell the word? Its etymological meaning, as a classicist will tell you, is the tendency of people to build and live in cities, and perhaps in the end that is all it means.

The computer game is apparently going strong in its sixth incarnation. About twenty years ago, in days of youth and limitless time, I poured days and nights into the second.  I mainly remember the importance of railways for being able to move soldiers around, and the manner of my final victory: having successfully divided up the world with my allies the Chinese (led by Mao Zedong), I then, when the moment was ripe, betrayed them and sent my 16-bit nuclear missiles like sweet silver raindrops to cascade upon their cities. In retrospect, I’d say it should have been called Wetiko II. Sitting Bull and the Sioux were always wiped out in the early stages, and I don’t recall an option to play as Genghis Khan.

I mainly remember the importance of railways for being able to move soldiers around, and the manner of my final victory: having successfully divided up the world with my allies the Chinese (led by Mao Zedong), I then, when the moment was ripe, betrayed them and sent my 16-bit nuclear missiles like sweet silver raindrops to cascade upon their cities. In retrospect, I’d say it should have been called Wetiko II. Sitting Bull and the Sioux were always wiped out in the early stages, and I don’t recall an option to play as Genghis Khan.